The Quaid needed to be discovered, his mystery unraveled. Not for his own sake because his place in history is assured and he does not stand in need of any praise from us. It should have been done because it was a necessity for the national psyche to be nourished by knowledge about the founder. How did he create country? What sacrifices went into making it? What odds did he face in the struggle? These are thought provoking words written by Mr. Z. A. Suleri in his book, My Leader. Almost similar are the ideas as described in Modern Muslim India and the Birth of Pakistan by Dr. S. M. Ikram: The Quaid-I-Azam’s superb qualities as a political leader are widely recognized. Justice has, however, not been done to him as a man. The grim struggle which he had to wage within a very limited time for the attainment of a near-impossible task left no room for kid-glove diplomacy, and the fact that his objectives ran counter to the wishes and sentiments of the British, the Hindus, the nationalist Muslims and the Punjab Unionists. Even ordinary Muslims have not been much more successful at understanding this giant, lonely figure. And how accurate is Mr. Suleri when he remarks in plain words there are three kinds of magnitude of action and attainment revolution, liberation, and creation. While Lenin brought about a Communist revolution, Mao Tse-Tung liberated his country from foreign bondage. But the Quaid created a country out of nothing.

There is no denying the fact that the evolution of Pakistan was not less than a miracle as it emerged on the globe against heavy odds with virtually no chance of success. Pakistan was brought about by a lean fellow who had struggled to bring the nation out of the quagmire of political depression and degradation with unusually firm convictions and unflinching determination. He exhibited such a moral fiber that even his enemies could not find a flaw in his character. He had an inflexible will infused with indomitable spirit. Neither any temptation nor any hazard from any quarter could shake his sincerity of purpose. He would neither compromise on principles nor employ chicanery to achieve his objects. According to Professor Stanley Wolpert, Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah was South Asia’s most brilliant Barrister, and an honest man, who also emerged as British India’s most remarkable political leader proving mire than a match for all of his Congress opponents including Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru by virtue of his total integrity, legal acuity and unwavering commitment to the Muslim League’s suit which he pressed through the last arduous decade of his devoted life, Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah sired the independent Nation-state of Pakistan. At another place he aptly remarked that Few individuals significantly alter the course of history; fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Muhammad Ali Jinnah did all three. Hailed as “Great Leader” (Quaid-i-Azam) of Pakistan and its first Governor General, Jinnah virtually conjured that country into statehood by the force of his indomitable will. Not even his political enemies, writes H. V. Hodson in his book, The Great divide, ever accused Jinnah of corruption or self-seeking. He could be bought by no one, and for no price. Nor was he in the least degree weathercock, swinging in the wind of popularity or changing his politics to suit the chances of the times. He was a steadfast idealist as well as a man of scrupulous honor. The fact to be explained is that in the middle of life he supplanted one ideal by another, and having embraced it clung to it with a fanatics grasp to the end of his days. Not many nations can take pride in their founding fathers and speak so highly of them. Leaders come in all physical and moral characteristics; only a few nations are blessed with people like Quaid-i-Azam, a towering figure among the Muslims who founded Muslim nationhood on ideological basis and achieved Pakistan single-handedly. The fact of the matter is that his place is not only as the creator of the modern Muslim nation but also with the great statesmen of the world.

He seemed to be a precocious child. The very decision he took to join Lincoln’s Inn unveils the acuity and maturity of his mind. When he saw an inscription on the entrance dedicated to the memory of the Prophet of Islam (S.A.W.), and his name included in the list of the great jurisprudents/law-givers, he instantly made up his mind to take admission in that institution to qualify for the bar. In London he suffered two severe bereavements, the deaths of his mother and his wife. He also got sad news of his father’s business on the verge of collapse. Nevertheless, he was patient and persevering and completed his formal studies and also delved into the British political system, frequently visiting the House of Commons where he listened to the speeches of statesmen like Gladstone, Lord Morley, Joseph Chamberlain, Balfour and others. Thus he learnt the art of parliamentary eloquence, which afterwards proved to be his strongest weapon. He was not a religious zealot but simply a Muslim in a broad sense and had little to do with sects. As he used to wear the finest suits available in the market, he was considered as one of the best-dressed persons of his time. Along with his highly impressive attire his whole personality was so charismatic so as to assure him entry in any of England’s stately homes and clubs. Many Viceroys were of the opinion that he was the best dressed gentleman they had ever met in India. His rationale, his rhetoric, his dedication and commitment to the cause were the factors that enabled him to fight in unique and peculiar style and with constitutional means the case of achieving independence for the down-trodden Muslims of the sub-continent who were so convinced by his qualities of leadership and his devotion to the cause of Pakistan that he was appropriately conferred the title of Quaid-i-Azam and Father of the Nation. They didn’t mind his western life style or his marriage to a Parsee girl.

He was introvert and modest like a woman. He remained unmarried and apparently indifferent to women until in 1918 when his interest in women was limited to his wife, Ruttenbai, the daughter of a Bombay Parsi millionaire whom he married in spite of tremendous opposition from her parents and others. On April 19, 1918, it was announced by the Statesman: Miss Ruttenbai, only daughter of Sir Dinshaw Petit, yesterday underwent conversion to Islam, and is today to be married to the Hon. M. A. Jinnah. Ruttenbai was only eighteen and the Quaid was then forty-one but she had resolved to marry the man of her choice, who had kindled in her heart the spark of true love. She was, of course, the  flower of Bombay, lively, witty, full of ideas and jokes and a brilliant conversationalist. Like her husband, she too championed the cause of the weak and stood up against oppression but unfortunately the bond of ineffable attachment proved too feeble to keep the two strong personalities, Jinnah and Ruttenbai together. The real cause of dissension between the two is not exactly known. Probably one reason was that the Quaid was too self-contained to receive instructions from others though paradoxically he never gave orders to his near and dear ones. Dina was his only daughter whom he loved with all the passion of a father. But when against his wishes, Dina married Neville Wadia, a young Parsi of Bombay, the Quaid was too displeased and disappointed to retain his fatherly relations. Ruttenbai who had left her husband early in 1928 expired the following year. The Quaid once more was all alone after he had faced the two most tragic episodes or say his family ruptures, which he endured with the calm and acquiescence like a Stoic. He didn’t disclose the anguish of his mind to anyone over these distressing separations. However, a pathetic incident is reported by a great short-story writer Saadat Hasan Minto in his short story Mera Saheb based on what he had heard from one of the Quaid’s chauffeurs, Muhammad Hanif Azad: Sometimes more than twelve years after Begum Jinnah’s death, the Quaid would order at dead of night a huge ancient chest to be opened, in which were placed clothes of his dead wife and his married daughter. He would raptly look into those clothes, as they were taken out of the chest and were spread on the carpets. He would gaze at them for long with articulate silence. One could clearly see him overwhelmed with emotions as his eyes would moisten spontaneously with tears.

flower of Bombay, lively, witty, full of ideas and jokes and a brilliant conversationalist. Like her husband, she too championed the cause of the weak and stood up against oppression but unfortunately the bond of ineffable attachment proved too feeble to keep the two strong personalities, Jinnah and Ruttenbai together. The real cause of dissension between the two is not exactly known. Probably one reason was that the Quaid was too self-contained to receive instructions from others though paradoxically he never gave orders to his near and dear ones. Dina was his only daughter whom he loved with all the passion of a father. But when against his wishes, Dina married Neville Wadia, a young Parsi of Bombay, the Quaid was too displeased and disappointed to retain his fatherly relations. Ruttenbai who had left her husband early in 1928 expired the following year. The Quaid once more was all alone after he had faced the two most tragic episodes or say his family ruptures, which he endured with the calm and acquiescence like a Stoic. He didn’t disclose the anguish of his mind to anyone over these distressing separations. However, a pathetic incident is reported by a great short-story writer Saadat Hasan Minto in his short story Mera Saheb based on what he had heard from one of the Quaid’s chauffeurs, Muhammad Hanif Azad: Sometimes more than twelve years after Begum Jinnah’s death, the Quaid would order at dead of night a huge ancient chest to be opened, in which were placed clothes of his dead wife and his married daughter. He would raptly look into those clothes, as they were taken out of the chest and were spread on the carpets. He would gaze at them for long with articulate silence. One could clearly see him overwhelmed with emotions as his eyes would moisten spontaneously with tears.

While many of the Quaid’s personal qualities are duly recognized, the grim struggle in which he was terribly engaged during the most important period of his life and the hostilities this struggle generated have obscured others. A few people know that apparently such a solemn and sober person was at heart so kind and affectionate, fair-minded and free from ill will towards other communities. A journalist like M.S.M. Sharma who was editor of the Daily Gazette, Karachi and was so bitter against Pakistan witnessed himself the tender-hearted Jinnah: In fairness to Jinnah I must record that he was the most shocked individual in Pakistan. He visited the Hindu refugee camps and at least at one of them, the iron-man lost his nerve and shed a few tears. The Quaid had really imposed such an iron discipline on himself that this account appears to be rather incredible. Evidence of tears is available from another source, Altaf Hussain, the Editor of the Dawn in his article, When Quaid Wept. He saw the Quaid quietly shedding tears over the sufferings of the Muslims in East Punjab.

His courage and boldness, moral as well as physical, steady nerve and remarkable will power were frequently tested but he always came out with flying colors. In 1943 he grappled with an assassin armed with a dagger. He firmly held his fist and didn’t leave him till the people gathered to save his life. In early 1947 when the All-India Muslim League was in session, all of a sudden a big group of Khaksars came rushing with their belchas to make an attempt on his life.

Meanwhile, the National Guards approached to his rescue and the police dispersed the Khaksars with the help of tear gas. Again the Quaid’s nerve was tested in virtually aggressive tone by Mountbatten. He threatened him that failing agreement, power might be transferred to the Interim Government. To his surprise, the Quaid remained very calm and composed. Mountbatten felt that his reaction was surprisingly abnormal and disturbing. It was certainly shrewd.

Good humor is said to be the seasoning of truth. The Quaid was amply endowed with good humor and wit. Here is an account of some exciting episodes. He was not impressed by Jawahar Lal Nehru’s claims about socialism. Once he jovially remarked, Pundit Nehru is a pendulum oscillating between Benaras and Moscow. Once he described the All Parties Leaders Conference as the Ditch army wherein everybody was a general and no soldier. During the Second World War, Joyace, son of a Britian Prime Minister, defected to Germany and made boastful broadcasts from Radio Berlin. He came to be known as Lord Haw-Haw. After the War he was captured and hanged. In 1946, Lord Pethic Lawrence, Secretary of State for India pointed out to the Quaid that a Muslim of the status of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad was opposed to his demands. The Quaid promptly retorted, Every nation has its Lord Haw-Haw.

It was reported in the press that Mr. M. K. Gandhi while offering his puja was not the least affected when a snake crawled around him in a circle. The Hindu press proclaimed that Mr. Gandhi was a Mahatma. Later on, the press urged the Quaid to comment on the incident. Mr. Jinnah said that there was nothing unusual in the snake not biting the Mahatma. After all, There is a professional etiquette. In 1947, Begum Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah fastened Imam Zamin on his wrist at the banquet hosted by the Governor. The Quaid asked, What is this for? the lady replied, Sir, it will protect from every evil influence. The Quaid promptly addressed Altaf Hussain, editor of The Dawn standing close to him, saying, Now I can face you. Once Mr. Gandhi asked Mr. Jinnah, How have you mesmerized the Muslims? The way you have hypnotized the Hindus, was the quick-witted answer. In December 1946, to a Swiss Journalist who remarked: Mr.Jinnah, were you not once in the Congress? the Quaid gave the shattering reply: I was in primary school once. In a jovial mood, Mr. Jinnah commented on the critics of Two-nation theory in these words: I am allowing full latitude to the majority community. They could wear their Dhoti, grow their Choti and eat their Dal-Roti.

The Quaid’s greatest passion was clarity, clarity of a point of view., writes Mr. Z. A. Suleri in his book, My Leader. To its articulation went not only his amazing power of analyzing but the whole might of his character. Every dot and comma mattered. He set himself such a high standard of clear thinking that only a pervasive person could mistake his meaning. Here is an instance of remarkable clarity of his expression:

It is extremely difficult to appreciate why our Hindu friends fail to understand the real nature of Islam and Hinduism. They are not religions in the strict sense of the word, but are, in fact, different and distinct social orders, and it is a dream that the Hindus and Muslims can ever evolve a common nationality, and this misconception of Indian nation has gone far beyond the limits and is the cause of most of our troubles and will lead India to destruction if we fail to revise our notions in time.

The Quaid has been occasionally accused of showing lack of courtesy. For instance, Campbell-Johnson refers to his hauteur and touchiness on one occasion quoting Ismay about a communication addressed by him to Mountbatten: It was a letter which I would not take from the king or send to a coolie. Actually his sharp reaction to certain individuals and on certain occasions was a part of his basic integrity and propensity to call a spade a spade. That is why when Maulana Abul Kalam Azad wanted to negotiate with him, his retort was extra-ordinarily blunt: I have received your telegram (which was addressed as confidential). I cannot reciprocate confidence. I refuse to discuss with you by correspondence or otherwise as you have completely forfeited the confidence of Muslim India. Can’t you realize you are made a Muslim show-boy Congress President to give it color that it is national and deceive foreign countries? You represent neither Muslims nor Hindus. The Congress is a Hindu body. If you have self-respect, resign at once. You have done your worst against the League so far. You know you have hopelessly failed. Give it up. Such was the dogged spirit that ultimately beat the enemy. In short, the truth is that the Quaid stands peerless in the galaxy of leaders. Amazingly the Hindus complimented him by wishing if only they had a single leader of his caliber, India’s destiny would have been different while the British paid him the tribute of never forgiving their Waterloo at his hands. Here is an interesting assessment detailed by Mrs. Sarojini Naido:

Never was there a nature whose outer qualities provided so complete an antithesis of its inner worth. Tall and stately, but thin to the point of emaciation, languid and luxurious of habit, Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s attenuated form is the deceptive sheath of a spirit of exceptional vitality and endurance. Somewhat formal and fastidious, and little aloof and imperious of manner, the calm hauteur of his accustomed reserve but masks for those who know him a nave and eager humanity, an intuition quick and tender as a woman’s, as a child’s. Pre-eminently rational and practical, discreet and dispassionate in his estimate and acceptance of life, the obvious sanity and serenity of his worldly wisdom effectually disguise a shy and splendid idealism which is the very essence of the man.

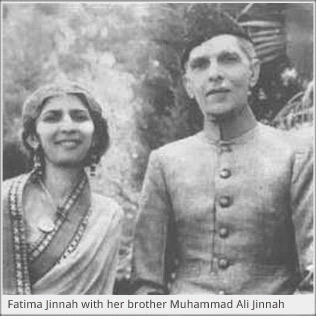

Quaid-i-Azam’s invariably kept his sister, Fatima Jinnah by his side in almost all political activities and social functions. This indicates his attitude towards women. He appealed to the youth of the nation to allow women to move about freely with a sense of security and respectability. He added that ladies not only should be allowed to participate in social, economic activities but also political activities so that Pakistan could emerge as a progressive, democratic and modern welfare state. Economic progress was a prime objective with him. He emphasized hard work and agricultural and technical education for the economic betterment of the country. Work, work and work and you are bound to succeed, was his advice to the whole of the nation. When we read the account of his long and serious illness, we are wonder struck to note his indomitable character and sheer will power with which he fought the killer disease and rejected the doctor’s advice to slacken the pace of his work. Still more amazing is the fact that he kept the matter of his illness a close secret. Sine the country was passing through a crisis, he thought it better not to divulge it so that the morale of the people is not affected. His sister recalls how she pleaded at oft-times with the Quaid to take a holiday and how he repeatedly replied, Have you ever heard of a General taking a holiday when the army is fighting for its very survival? On September 6, 1948, the Doctor asked Miss Fatima Jinnah to shift the Quaid to Karachi immediately. When this was conveyed to the Quaid by his sister, he agreed without any hesitation and said, Yes, take me to Karachi. I was born there, I want to be buried there. He closed his eyes, writes Miss Jinnah, and I just could not leave his bedside. He was soon asleep but terribly restless. He was mumbling, Ma Bapa Kashmir refugees Bapa-Fati. According to Col. Illahi Bukhsh, the Quaid turned his eyes in a fit of faintness and murmured, Allah Pakistan.

Quaid-i-Azam’s invariably kept his sister, Fatima Jinnah by his side in almost all political activities and social functions. This indicates his attitude towards women. He appealed to the youth of the nation to allow women to move about freely with a sense of security and respectability. He added that ladies not only should be allowed to participate in social, economic activities but also political activities so that Pakistan could emerge as a progressive, democratic and modern welfare state. Economic progress was a prime objective with him. He emphasized hard work and agricultural and technical education for the economic betterment of the country. Work, work and work and you are bound to succeed, was his advice to the whole of the nation. When we read the account of his long and serious illness, we are wonder struck to note his indomitable character and sheer will power with which he fought the killer disease and rejected the doctor’s advice to slacken the pace of his work. Still more amazing is the fact that he kept the matter of his illness a close secret. Sine the country was passing through a crisis, he thought it better not to divulge it so that the morale of the people is not affected. His sister recalls how she pleaded at oft-times with the Quaid to take a holiday and how he repeatedly replied, Have you ever heard of a General taking a holiday when the army is fighting for its very survival? On September 6, 1948, the Doctor asked Miss Fatima Jinnah to shift the Quaid to Karachi immediately. When this was conveyed to the Quaid by his sister, he agreed without any hesitation and said, Yes, take me to Karachi. I was born there, I want to be buried there. He closed his eyes, writes Miss Jinnah, and I just could not leave his bedside. He was soon asleep but terribly restless. He was mumbling, Ma Bapa Kashmir refugees Bapa-Fati. According to Col. Illahi Bukhsh, the Quaid turned his eyes in a fit of faintness and murmured, Allah Pakistan.

Father of the Nation, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s achievement as the founder of Pakistan, dominates everything else he did in his long and crowded public life spanning around 42 years. By any standard, he led an eventful life. His personality was multidimensional and his achievements in other fields were diverse. And he played several roles with distinction at one time or another. He was one of the greatest legal luminaries India had produced during the first half of the century, an `ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity, a great constitutionalists, a distinguished parliamentarian, a top-notch politician, an indefatigable freedom-fighter, a dynamic Muslim leader, a political strategist and, above all one of the great nation-builders of modern times. Very few national leaders like Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah maintained and manifested their trends, temperament and traditions till the last moment of their life. What, however, makes him so remarkable is the fact that he created a nation out of an inchoate and down-trodden minority and established a cultural and national home for it. Indeed, his life story constitutes the story of the rebirth of the Muslims of the subcontinent and their spectacular rise to nationhood like a phoenix.

Bibliography

- Allana, G., Quaid-i-Azam: The Story of a Nation, Ferozesons, Karachi, 1967

- Ali, Chaudhri Muhammad, The Emergence of Pakistan, Services Book Club, 1988

- Beg, Aziz, Jinnah and His Times: A Biography, Babur & Amer Publications, Islamabad, 1986.

- Bolitho, Hector, Jinnah, John Murray, London, 1954

- Hodson, H. V., The Great Divide: Britain India Pakistan, Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1985

- Ikram, S. M., Modern Muslim India and the Birth of Pakistan, Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, Lahore, 1970

- Minto, Saadat Hasan, Ganje Farishte, Maktaba-e-Jadid, Lahore, 1955

- Munawwar, Muhammad, Dimensions of Pakistan Movement, Services, Rawalpindi, 1993

- Stephens, Ian, Pakistan, Ernest Benn, London, 1963

- Suleri, Z. A., My Leader, Institute of Islamic Culture, Rawalpindi, 1992